House GOP Tax Plan Sticks With Big Corporate Cuts

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act seeks the biggest transformation of tax code in more than 30 years; leaves top individual tax rate at 39.6%

POLITICS

By Richard Rubin | original link

WASHINGTON—House Republicans unveiled the details of the biggest transformation of the U.S. tax code in more than 30 years, calling for deep cuts in business-tax rates and starting a race to pass the complex legislation by year’s end. (Follow live coverage of the GOP tax plan.)

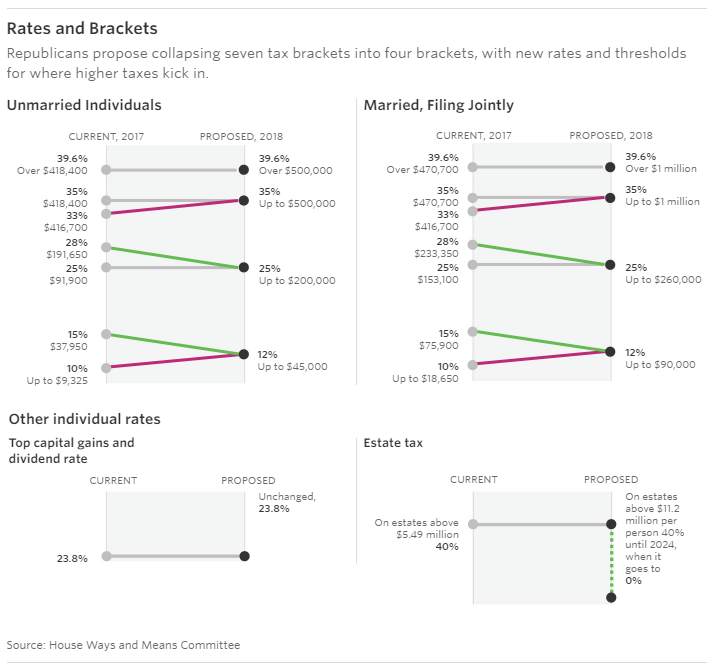

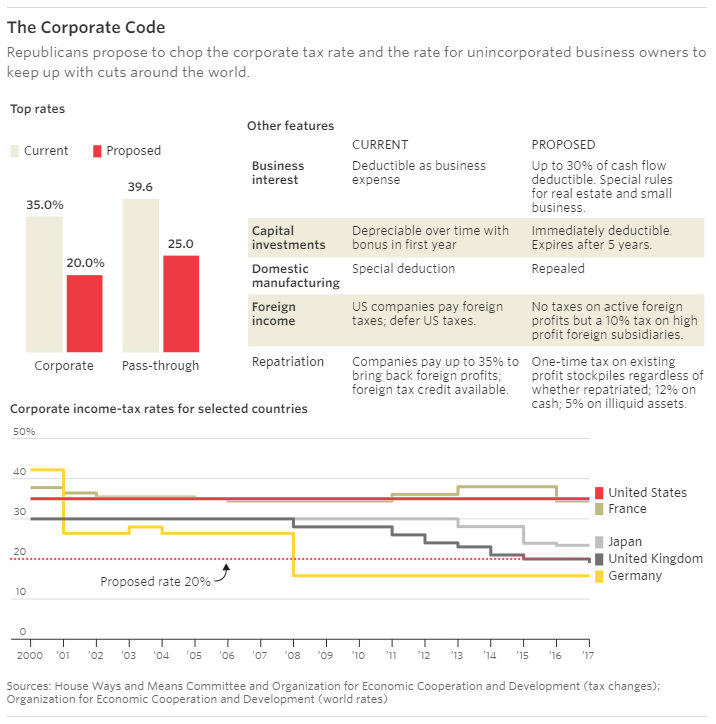

The plan calls for chopping the corporate tax rate to 20% from 35%, compressing individual income-tax brackets, and eventually repealing the estate tax. The bill’s ambitions—along with the slim Republican margins in the House and Senate—could also be what stop it.

To partly offset that lost revenue from rate cuts, Republicans plan to curtail the deductions individuals take for state and local tax payments and mortgage interest and the ones businesses get for the interest they pay on debt. The proposal also repeals personal exemptions, which filers take based on family size to reduce their taxable income.

That combination creates winners and losers, and people and businesses whose tax bills might rise began mobilizing to block or alter the bill.

Many House Republicans rallied around the plan, but it also ran into immediate opposition and skepticism, including wariness from some usual GOP allies. The National Federation of Independent Business, the influential lobbying group for small businesses, said it couldn’t back a bill that “leaves too many small businesses behind.”

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce applauded the measure but said “a lot of work remains to be done.”

Manufacturers, retailers, wholesalers and conservatives largely backed the plan, while home builders and real-estate agents prepared to fight proposals that reduce benefits for homeownership. Democrats panned the bill, and some GOP lawmakers from high-tax states said they were opposed to the bill because of changes to the state and local deduction.

“The special interests will distort the facts, the lobbyists will try to save their special deals, and some in the media will unfairly report on our efforts,” President Donald Trump said in a statement.

“But my administration will work tirelessly to make good on our promise to the working people who built our nation and deliver historic tax cuts and reforms—the rocket fuel our economy needs to soar higher than ever before.”

The plan, named the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, calls for leaving the top individual tax rate at 39.6%, but pushing the income threshold for that rate to $1 million for married couples from $480,050. The House Ways and Means Committee plans to consider the bill next week with the aim of turning it into law by Christmas and having most of it take effect in 2018 and be reflected on tax returns filed in 2019.

Republicans view the tax bill as essential to their political futures and their best chance for a legislative victory in Mr. Trump’s first year in office. Taken altogether it amounts to just over $300 billion in tax reductions for individuals, a $172 billion estate tax cut and about $1 trillion for businesses, a mix Republicans say will improve an archaic business tax code and put money in the pockets of households.

Yet, it faces a challenging path to completion in a Congress contending with many competing interests, as Thursday’s reactions showed. The tax bill was revised repeatedly in the final days before its release and looks sure to face additional changes as the GOP tries to shape it into a law. It already bears the marks of political compromises large and small, in addition to budgetary contortions needed to avoid creating larger and long-lasting budget deficits. For example, incentives for business investment lapse after five years and so does a new $300 per person credit for filers, their spouses and non-child dependents such as college students. Full repeal of the estate tax doesn’t kick in until 2024.

Those moves were necessary because a budget blueprint agreed upon by the Senate and the House constrains the tax overhaul to a cost of $1.5 trillion over a decade. They need to hit that target and avoid larger budget deficits beyond that to qualify for legislative rules that allow them to pass a bill by a simple majority in the Senate without votes from Democrats. They are also constrained by the party’s desire to set the corporate tax rate at 20% and make it permanent, a provision that by itself lowers revenue by $1.46 trillion over a decade.

Mr. Trump is hoping to win over some Democrats in the Senate, but lawmakers in the opposition party largely criticized the plan Thursday.

Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer (D., N.Y.), said Democrats will focus on issues like the loss of deductions for state and local taxes, medical expenses and student loan interest.

“The more the public sees this bill, the less they will like it. And I think that’s the reason our Republican colleagues are rushing this bill,” he said in an interview. “The hard right, which cried about deficit reduction for so long, has abandoned it as soon as they get tax cuts for the wealthiest and the most powerful.”

Republicans have their own internal divisions to manage as they try to advance the plan. They are seeking more than $5 trillion in rate cuts over a decade and need to find offsetting provisions, setting them up for tough trade-offs that will leave some in the party displeased. Republicans have spent months trying to solve that math problem, looking for tax breaks to repeal without disturbing the slim political coalition they need to pass a bill.

Republican leaders began the hard work of selling their plan, starting with a meeting of lawmakers Thursday morning and a White House event in the afternoon. They are soliciting reaction from business groups, particularly on complicated and novel changes to the taxation of corporate foreign income and pass-through businesses such as partnerships. Those areas contain huge potential problems and some Republicans were already asking for changes on Thursday.

They intend to work quickly. The first crucible is the House Ways and Means Committee, which will begin considering the plan Monday.

“We’ll be in listening mode all throughout the code,” said the bill’s author, Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady (R., Texas). “We are following the Reagan example here. Go bold. Listen. Make adjustments, but keep the process going forward.”

After that come the tougher challenges of reaching a House majority and melding this bill with a separate Senate plan scheduled for release as soon as next week.

The plan hits many Republican goals. It nearly doubles the standard deduction, pushes people away from itemizing their deductions, lowers business tax rates, repeals the alternative minimum tax, and eliminates many tax credits, deductions, and exclusions, such as breaks for moving expenses and employee achievement awards.

But the plan stops short of touching other popular tax breaks that were being considered for change, such as the ability of individuals to park up to $18,000 a year in pretax funds into 401(k) savings accounts. It also doesn’t move the top tax rates on capital gains and dividends.

Republicans used at least a few budgetary maneuvers to squeeze the plan inside its constraints. For instance, different inflation measures limit some costs. They also changed some provisions during negotiations to add revenue. A new one-time tax rate on U.S. companies’ stockpiled foreign profits will be significantly higher than in previous Republican plans, generating money to meet the $1.5 trillion target. The bill would apply a 12% tax rate to cash in foreign subsidiaries and a 5% tax rate to illiquid investments.

Income-Tax Rates

The bill collapses the current seven individual tax brackets into four: 12%, 25%, 35% and 39.6%. The new bottom tax rate covers more income than the current 10% and 15% brackets do, meaning lower taxes for many middle-income households.

Many upper-income households could face a higher marginal tax rate under the House bill, which pushes some from a 33% bracket into 35%. Whether they see actual tax increases would depend on particulars, and full estimates aren’t available yet.

Political Land Mines

Political Land Mines

Meanwhile, there are political land mines scattered in the plan, some easy to see and others that businesses and advocates will likely unearth in the coming days and use to argue against the plan. For example, the proposal repeals an itemized deduction for medical expenses, a crucial provision to households with extraordinary health-care costs. It also repeals the tax credit for adoption and the deduction for student-loan interest.

The bill also limits the home mortgage-interest deduction. For new home purchases, interest would be deductible only on loans up to $500,000, down from $1 million in the current tax structure. If enacted, that rule would apply retroactively to mortgages on home purchases starting Friday. Existing loans, including refinancings, would be grandfathered under the $1 million limit. The bill would end the mortgage-interest deduction on second homes and prevent the interest deduction on new home-equity loans.

“Eliminating or nullifying the tax incentives for homeownership puts home values and middle-class homeowners at risk, and from a cursory examination this legislation appears to do just that,” said William Brown, president of the National Association of Realtors.

Because of the larger standard deduction, fewer people would have a tax incentive to make charitable donations. Many charity groups had pushed for a more widely available deduction, but Republicans decided not to expand the charitable deduction to people who don’t itemize their deductions.

Fewer Deductions

The bill eliminates other deductions, including the ability of businesses to deduct certain executive compensation above $1 million, which they can now take for performance-based pay. Life insurers would lose some tax breaks. Banks with assets exceeding $50 billion would get no deduction for certain payments to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

Tax-exempt bonds could no longer be used to build professional sports stadiums. Private universities with assets exceeding $100,000 a student would pay a new 1.4% excise tax on their net investment income. Businesses would no longer be able to deduct entertainment expenses, though today’s rules for business meals would remain.

Pass-Through Business

One of the most closely watched areas is the taxation of pass-through businesses such as S corporations and partnerships. Republicans promised them a 25% rate, but also said they would create guardrails to prevent people from turning what would otherwise be wage income taxed at up to 39.6% into business income taxed at a lower rate.

Passive owners of pass-through businesses would get the 25% rate, but those actively involved in the business would have a different standard. The bill starts with the presumption that 70% of that pass-through income is attributable to labor and would be taxable at higher individual income-tax rates. For some that would create a blended top tax rate of about 35%, which some saw as not low enough.

“This bill leaves too many small businesses behind,” said Juanita Duggan, president of the National Association of Independent Business, which represents small businesses. “We are concerned that the pass-through provision does not help most small businesses.”

For professional services firms, including lawyers and financial-services professionals, the default rate would be 100% labor income, meaning they would get none of the benefit of the 25% tax rate for pass-through businesses.

The bill gives business owners leeway to argue that more of their income should be taxed at lower rates because of capital they have invested in their firms. That could in turn complicate their tax returns and the filing process.

Multinational Corporations

Meanwhile, there are big changes in store for multinational companies. U.S. companies would, generally, no longer pay taxes on their active foreign income, a move corporations and Republicans say is important to stay competitive with companies from lower tax countries. To prevent companies from shifting profits abroad, the bill creates a new 10% tax on U.S. companies’ high-profit foreign subsidiaries, calculated on a global basis.

The plan also imposes new restrictions on foreign companies operating in the U.S. They would face a tax of up to 20% on payments they make abroad from their U.S. operations. That is designed to prevent them from loading up their U.S. operations with deductions and pushing profits to low-tax jurisdictions. Companies could lower those taxes by agreeing to have more of their operations in the U.S. tax system.

Many companies would face a new limit on their interest deductions, which would be capped at 30% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, which is a measure of cash flow. Real-estate firms and small businesses would be exempt from that limit.

Child-Tax Credit

For individuals, one potential flashpoint is an expanded child tax credit, which isn’t as large or generous to low-income families as a version proposed by Sens. Marco Rubio (R., Fla.) and Mike Lee (R., Utah). The child credit, along with the larger 12% bracket, is crucial to limiting the number of low-income and middle-income families who see tax increases due to the bill. One reason they might still see higher bills is because the bill eliminates personal exemptions.

The House bill takes the child credit from $1,000 to $1,600, below the $1,800 or $2,000 that Messrs. Rubio and Lee want. The House bill also creates a new $300 credit for each person in a filer’s family who isn’t a child, including the primary taxpayer and non-child dependents such as college students. For example, a married couple with two children in 2018 and making $60,000 would see their tax bill drop to $472 from $1,608.However, those $300 credits expire after 2022.

The House bill also expands the child credit for the upper-middle class. Currently, the credit starts phasing out for individuals with incomes above $75,000 and married couples with incomes above $110,000. Under the House bill, those thresholds move up to $115,000 and $230,000.

The estate-tax exemption, set for $5.6 million per person and $11.2 million per married couple, would double immediately. The tax would get repealed starting in 2024.